The History of Halton’s Science and Industry Heritage

Imagine standing on the banks of the River Mersey in the early 1800s, where smoke from towering chimneys signalled a new era of progress. The luxury spa destination of Widnes and Runcorn where families came to relax and bathe, quickly became the beating heart of Britain’s Industrial Revolution thanks to its strategic waterways and nearby raw materials. Halton quickly became a hub known for chemical innovation, soap manufacturing and facilitating global trade. Laying down the foundations for modern science and industry.

The Bridgewater Canal: Gateway to Global Trade

When the Bridgewater Canal opened in 1776, it didn’t just connect Runcorn and Widnes to Liverpool and Manchester, it connected Halton to the world. The waterway became the lifeline of Britain’s Industrial Revolution, carrying Mersey Flats loaded with goods towards the Atlantic Ocean via the River Mersey.

By the late 18th century, Runcorn’s port was the epicentre of the UK’s trading routes, transforming the town into a booming hub of trade and innovation. The canal wasn’t just a route; it was a catalyst for growth, fuelling the rise of soap and alkali companies that would shape Halton’s identity for generations.

[Wet Docks Locks in Widnes]

Halton’s Industrial Soap Manufacturing and the Rise and Fall of the Leblanc Process

In the early 1800s, two ambitious entrepreneurs, John Johnson and Thomas Hazlehurst, saw an opportunity to capitalise on soap and alkali production, using the Leblanc process. A groundbreaking method for artificially manufacturing soda ash (sodium carbonate), an essential ingredient used in cleaning products, paper manufacturing and glass production.

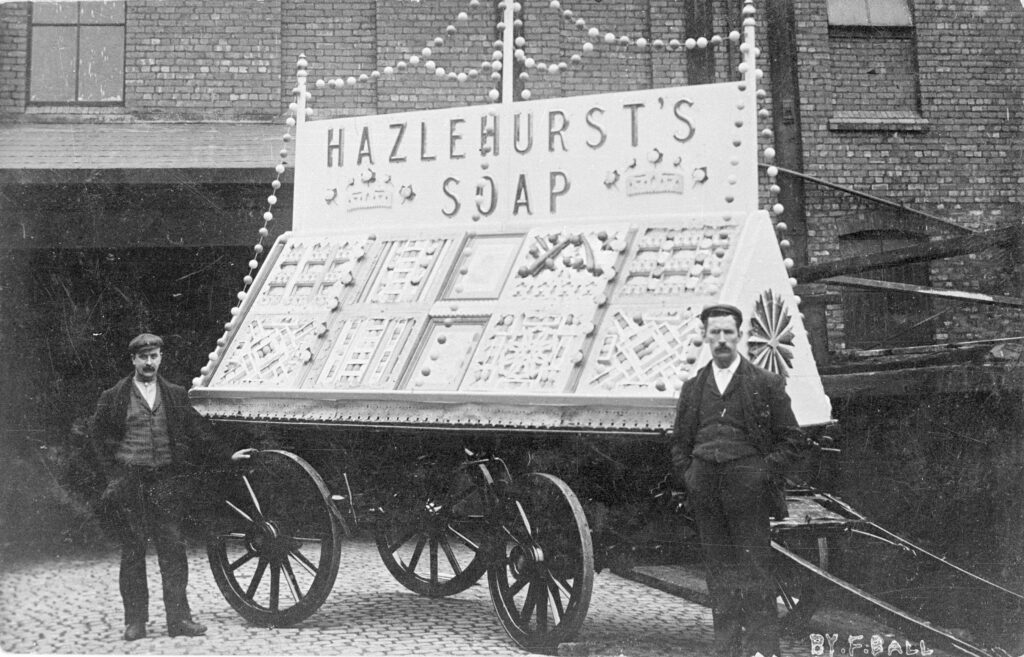

[Decorated horsedrawn cart with a display of Hazlehurst’s soap products for a parade]

In 1803 John Johnson established Johnson’s, Runcorn’s first successful soapmaking business and by 1816, Thomas Hazlehurst followed entering the market with Hazlehurst & Sons. Their soaperies faced each other divided by the Bridgwater Canal so barges could carry goods to global markets such as America and the far east.

However, success came at a cost. Britain’s 1696 salt tax and soap excise duty made production expensive, soaperies had to pay 3p per pound of soap produced to the government and common salt was charged thirty times its original value. The abolishment of the salt tax in 1825 caused industrialists to start using the Leblanc process on a much larger scale. Alkali became cheap and by 1932 Hazlehurst & Sons and Johnson’s were listed in the UK’s top 20 largest soap manufacturers. Runcorn’s skyline became dominated by their chimneys.

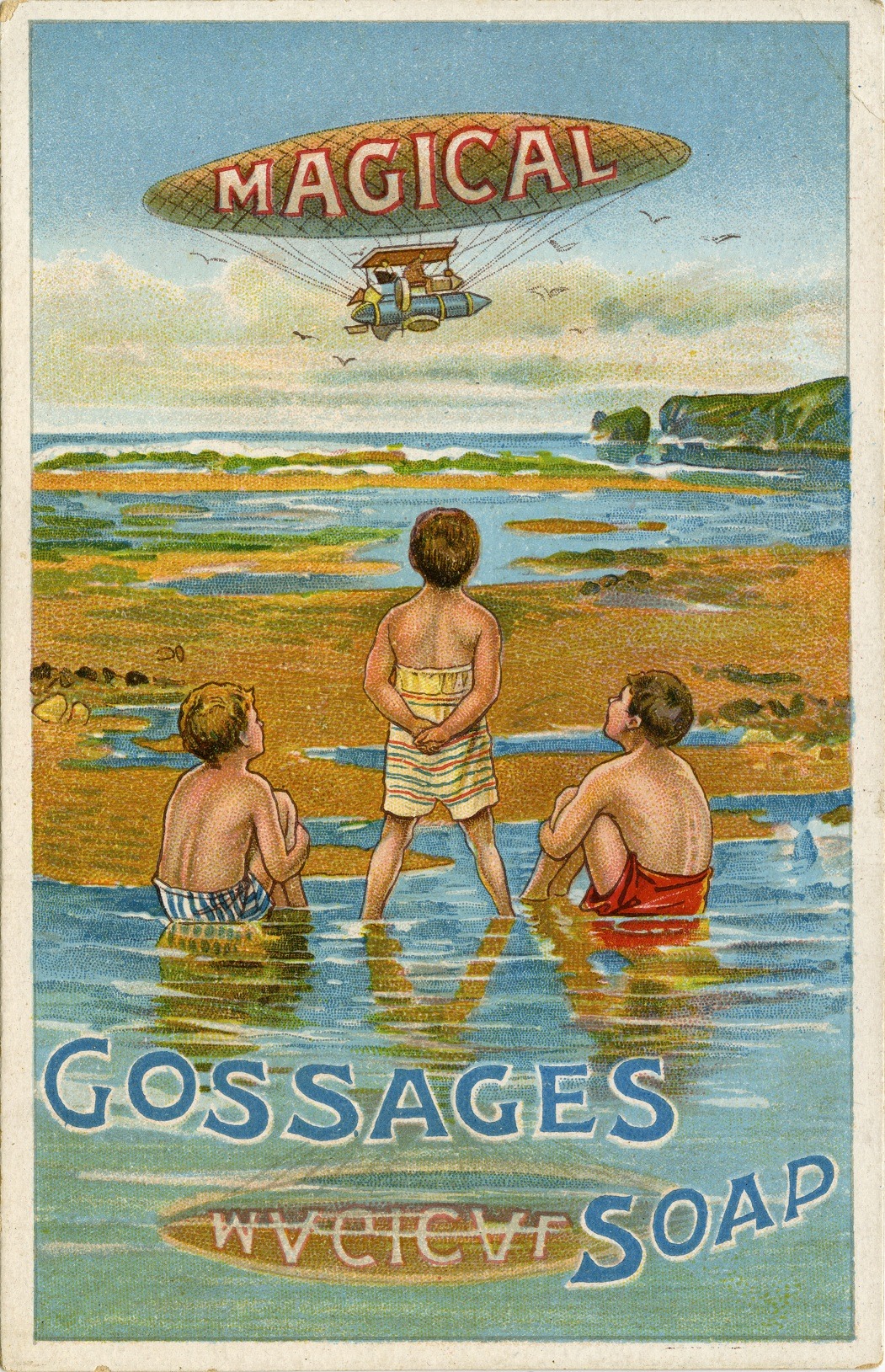

Halton’s desirable location of production and exportation attracted new talent like William Gossage, who moved to Widnes after his British Alkali business failed. Hoping to differentiate the soap market, be started experimenting with liquid glass and soda ash, where he discovered how to make soap cheaper. As a result, Gossage started up William Gossage & Sons and started experimenting with pigments, creating the now iconic mottled soap. His invention earned international acclaim, and by the 1860s, Gossages was responsible for half of Britain’s soap exports.

[Gossages Magical Soap Advertisement]

[Gossages world renowned mottled soap]

Environmental Challenges and the Alkali Act

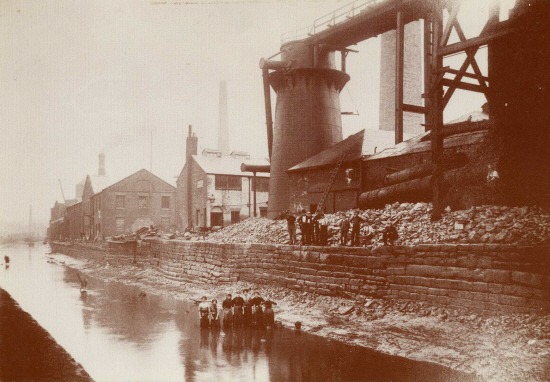

As profits soared and chemical factories expanded, Halton’s industrial empires flourished. Companies such as Johnson’s bought copper smelteries, quarries, tanneries, shipyards, salt mines and coal pits to maximise production and control supply chains. However, wealth and power came at an environmental price. The Leblanc process, the backbone of alkali production, was leaving a toxic footprint. Sulphuric waste was dumped into Widnes’ wetlands by factories and clouds of hydrochloric acid chocked the air of the once picturesque villages.

The industrial transformation was grim, vibrant landscapes turned grey, wildlife vanished and Runcorn’s reputation as a spa retreat evaporated under a haze of pollution that caused inadequate sanitation, poor living conditions and even death. Halton’s industrial triumph has created an environmental tragedy, one that would haunt the area for decades.

[Photograph boys and girls collecting coal in the de-watered Bridgewater Canal next to the Runcorn Soap and Alkali works during 1880s]

In 1863, the UK government stepped in to control hydrochloric acid, passing the Alkali Act, the first UK law designed to reduce emissions. The legislation required all soda manufacturers to capture and condense hydrochloric acid instead of just releasing them into the atmosphere. Most manufacturers started using the Gossage acid tower, an invention made by George Gossage in 1836 when he owned British Alkali Works.

The Act helped clean the air and marked the beginning of environmental regulation in Britain. In that same year, German-born British chemist Ludwig Mond moved to Widnes with an innovative idea to recover sulphur from alkali waste. His breakthrough could save nearly half of the sulphur waste and turn pollution into product. He was hired by the largest alkali manufacturer in Widnes at the time, John Hutchington & Co as an independent salaried scientist. Soon Mond patented his design and sold it widely which reshaped the industry, making him extremely rich.

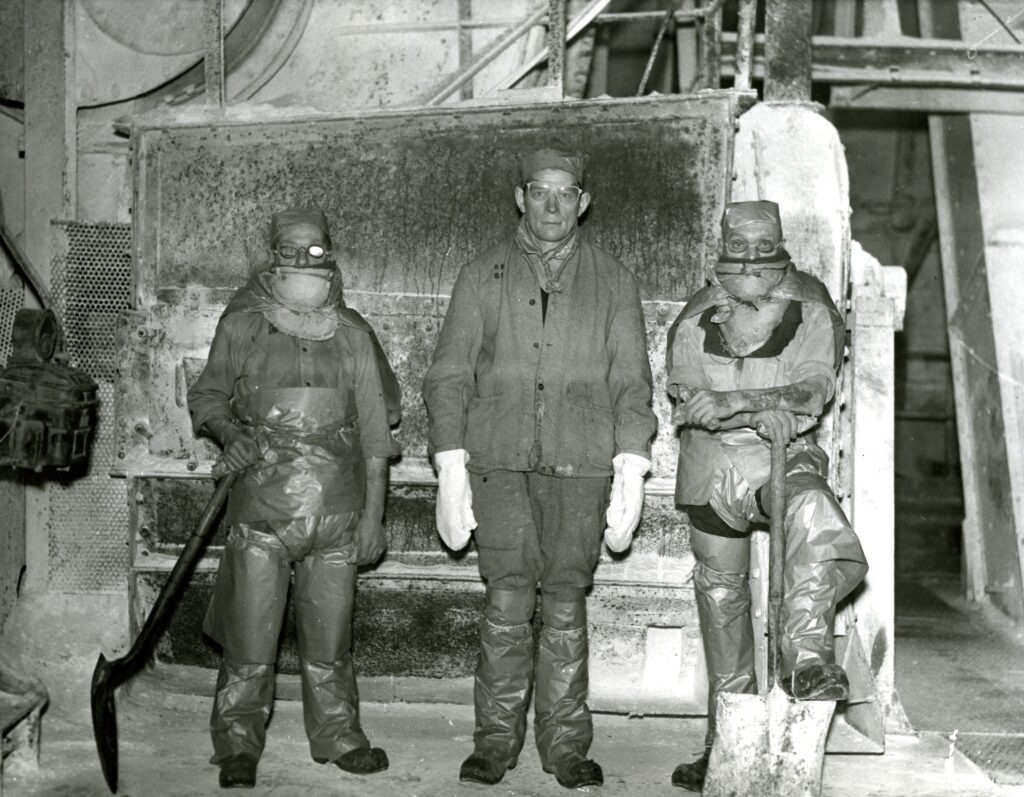

Images digitised during the Halton Heritage Partnership ‘Working Lives’ HLF project (2015-16)

[Bleach Workers at an Alkali Factory in Halton]

During his time in Widnes, Mond met John Tomlinson Brunner, Hutchinson’s chief clerk. Their partnership sparked a revolution: together they became pioneers for adopting the Solvay process, a cleaner and cheaper alternative to Leblanc. In 1873 they established Brunner, Mond & Co, a venture that would later evolve into Tata Chemicals Europe in 2011.

Brunner Mond and the Rise of Chemical Giants

By the 1860s, the Johnson brothers were one of the largest manufacturers in Britain and helped govern Runcorn. Their empire stretched from soap works to tanneries and they even built historical landmarks like Runcorn Town Hall and Bank Chambers. Some sources even suggest that they supplied leather for Queen Victoria’s armies. However, their striving ambition for more power and profit caused their annihilation. In a daring bid to supply the Confederate States during the American Civil War, the Johnson brothers gambled everything on breaking the Union blockade. Their first run made a fortune; the second in 1865 ended in disaster, most of their ships were lost, fortunes sank, and the company went bankrupt.

Hazlehurst & Sons, Gossages, other competitors and former employees such as Charles Wigg absorbed Johnson’s assets to form the Runcorn Soap and Alkali Company. However, the tide was turning for Leblanc businesses as the chemical industry faced an existential threat: Brunner Mond & Co’s cleaner, cheaper and licensed Solvay process was rewriting the rules of chemical production. Manufacturers were impacted by overproduction, American tariffs and relentless competition squeezed profits. For Leblanc businesses, a radical decision had to be made, merge into something bigger or cease to exist.

In 1880, Hazlehurst & Sons, the Runcorn Soap and Alkali Company and other major Leblanc business across Halton and Britain merged to form the largest chemical company in the world, United Alkali Company (UAC).

Realising the necessity to diversify and innovate away from the Leblanc process, the UAC built a new Central Laboratory in Widnes which was completed in 1892, signalling a future driven by science. Three years later, the Manchester Ship canal opened which further improved Halton’s connectivity and fuelled a temporary boom in business and population.

Castner-Kellner and Chlor-Alkali Breakthrough

During the late 19th century and early 20th century, the Solvay process started to become industry standard. What once was a borough of diverse manufacturing, focus narrowed to four key exports: tanning, chemicals, soap and stone.

Industrialisation caused Runcorn sandstone to become a desired commodity that travelled far beyond Cheshire. In Britain the sandstone had helped build historic landmarks across Britain, including Liverpool Corn Exchange, Manchester Cathedral and even Roman fortifications in Conwy. By the 1900s it was shaping the docks of New York, San Francisco and Galveston, Texas.

During this period, Halton’s tanning industry experienced significant expansion. By 1914, Highland alone was processing approximately 5,000 hides per week, representing a remarkable increase from the mere 50 hides handled per week in 1888.

After the turbulence of the 1890s, Halton’s chemical industry roared back to life. At the forefront of this revival was the newly formed Castner-Kellner Alkali Company, a strategic alliance between Hamilton Castner, Karl Kellner, and the Solvay Company. Their breakthrough? The Castner-Kellner process, which effectively founded the chlor-alkali industry. Designed to meet the growing demand for chlorine and high-purity caustic soda, the method relied on electrolysis of brine in mercury cells, representing a significant scientific leap forward. By 1897, Castner-Keller constructed the UK’s first major industrial-scale electrolytic plant at Weston Point, Runcorn, cementing Halton’s future as a global leader in chemical manufacturing and electrochemical engineering.

During the buildup to World War One, the UAC started experimenting with methods to rival Brunner Mond & Co’s Solvay process after their negotiations with Castner-Kellner failed. By 1907, the Central Laboratory had developed processes for developing twenty-four organic chemicals, which became increasingly important to British and international markets in the twentieth century. On 4th August 1914, World War One was declared, causing the UAC and Central Laboratory’s focus to shift towards, producing and researching explosives and chemical warfare agents such as mustard gas.

As alkali production stagnated in favour of electrochemical engineering, Halton’s internationally award-winning soap manufacturers gained interest from large chemical organisations. In 1911, the Lever Bros of Warrington, who produced Sunlight Soap acquired Hazlehurst & Sons and turned it into Camden Tannery, whereas Brunner-Mond bought Gossages, who would later sell the organisation to Unilever in 1932 after the Lever Brothers merger with Margarine Unie. As a result, Unilever became the world’s largest amalgamation, Halton’s soap and alkali industry ceased to exist as production moved up the River Mersey to Port Sunlight. Gossages old factories were demolished, the derelict offices formed the core of Catalyst Science Discovery Centre, and the wasteland became Spike Island, which in the present day is thriving with wildlife.

[Boats docked at Gossages Soap Works in 1933]

In the build-up to the Second World War, Castner-Kellner started to align itself with Brunner Mond and by 1920 Castner-Kellner had become a subsidiary of Brunner, Mond & Co by exchange of shares. 6 years later, Brunner Mond merged with the United Alkali Company, Nobel Explosives and British Dyestuffs Corporation to form one of the world’s largest chemical companies Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI).

ICI and 20th Century Innovation

ICI’s extensive operations across Runcorn and Widnes, catalysed technological and industrial growth throughout the 20th Century to firmly establish the region as Britain’s central hub for scientific innovation, chemical research and chlorine production.

During World War Two, the Central Laboratory in Widnes once again played a vital and highly classified role in Britain’s war effort, contributing to the development of poisonous gas and conducting uranium isotope research for the UK’s nuclear program.

In the post-war years, ICI plants in Halton continued to focus on chemicals research. Notably, in 1955, Charles Walter Suckling first synthesized the anaesthetic halothane while working at ICI’ Central Laboratory.

After a series of construction projects to improve Halton’s connectivity. In 1964, Runcorn was designated as a New Town, attracting a variety of manufacturers including General Motors. These manufactures were the largest employers in Halton and shaped the local community, influencing housing, transport and infrastructure.

[Widnes Railway Bridge across Spike Island]

By the early 1990s ICI started to demerge the company because of increasing competition, internal complexities and a strategy to move towards more specialised chemicals. In 1991 the company divested its soda ash division to Brunner Mond and by 2001, INEOS had completed its acquisition of ICI’s chlor-chemical businesses.

Halton Today: A Modern Industrial Hub

Today, Halton retains its status as the UK’s most diverse chemical production region, employing over 50,000 people across over 500 facilities and enterprises. At its core is INEOS’ Runcorn complex, home to one of Europe’s largest membrane electrolysis units and serves aa a leader in chlor-alkali production and clean hydrogen projects. Remarkably, chemicals produced at Runcorn are used to purify 98% of the UK’s water supply. Beyond chemical production, the region also accommodates major operations, with Diageo overseeing bottling, canning and kegging of Guiness at its major packaging facility in Runcorn.

Complementing Halton’s industrial strength are two strategic assets: 3MG Widnes Freeport and Sci-Tech Daresbury. As one of only eight freeports in England, 3MG Widnes offers unrivalled connectivity, with direct links to the UK’s rail and motorway network, making it a prime location for logistics, imports and exports. Additionally, it plays a key role in the emerging hydrogen economy by supporting low carbon fuel and infrastructure projects.

Meanwhile, Sci-Tech Daresbury stands out as one of England’s leading science and innovation campuses, driving growth in clean energy, advanced engineering and digital technology sectors.

From the smoke-filled skies of the Industrial Revolution to today’s cutting-edge science and sustainability projects, Halton’s story is one of manufacturing, innovation and advanced research. What began as a hub for soap and alkali production has evolved into a dynamic ecosystem powering clean energy, technological research and global trade that continues to shape Britain’s industrial future.

Plan your visit to the Catalyst Science Discovery Centre to experience the story of Britain’s chemical revolution for yourself. Also explore our Halton Heritage Guide taking you on a journey through the borough’s rich heritage and famous landmarks!

Images courtesy of Halton Heritage Partnership.